For Americans who want to experience a tropical Pacific vacation where they can sit under palm trees and dive in coral reefs, American Samoa is a popular choice, you don’t even need a passport to go! Unfortunately, American Samoan reefs have taken a beating in the last few decades, and more harm may come to the reefs this year.

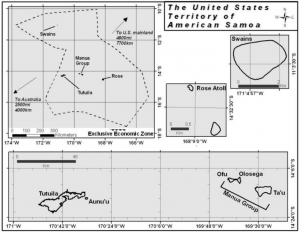

American Samoa is a small collection of tropical islands in the South Pacific composed of the five islands and two atolls. The largest island is Tutuila, with tiny Aunu’u nearby. About a hundred kilometers to the east is the Manua group, containing the islands Ofu, Olosega, and Ta’u. Scattered several hundred kilometers out are the atolls, Rose Atoll to the east, and Swains Island to the north [1].

Map of American Samoa, from Lundblad et al.

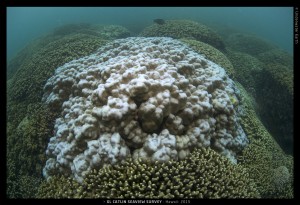

Samoan reefs are known to be some of the most resilient in the world, even so, they have not been immune from many of the troubles coral reefs around the word have been facing. The reefs suffered greatly from an outbreak of crown of thorns starfish (COTS) in 1978, which decreased coral cover by as much as 68%. The reefs have been damaged by a half-dozen hurricanes since the 1980’s, and have dealt with extreme low tides on three occasions since 1998. In 1994, 2003, and 2004, American Samoan reefs suffered bleaching events [2]. Bleached corals have also been seen in 2014 and 2015 [3].

Coral bleaching captured between December 2014 and February 2015, from http://www.globalcoralbleaching.org/

Part of the American Samoan reefs’ resilience may come from their natural tolerance of high temperatures. For instance, Acropora corals near Ofu island have been seen weathering temperatures over 32°C [4].

For the more than 200 coral species found in reefs in American Samoa, climate change caused by humans puts them at risk for bleaching and leaves them susceptible to disease [5]. Sick corals are bad news to industries such as tourism and fishing, and particularly impact native peoples who rely on the sea.

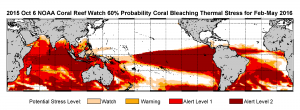

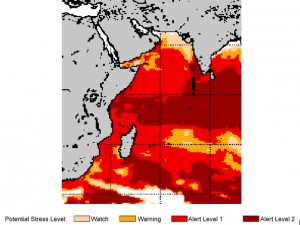

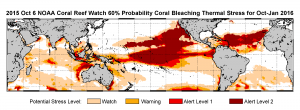

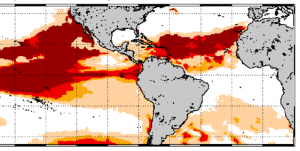

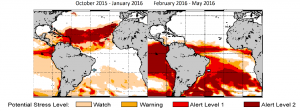

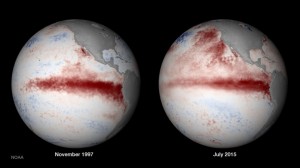

This year, reefs in American Samoa are threatened once again. Bleaching has already been observed in late 2014 and early 2015 [3]. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Coral Reef Watch project, American Samoa and the surrounding oceans are facing a warning for mass coral bleaching events [6]. 2016 may see some tough times for reefs in American Samoa.

NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch warnings for the South Pacific. From http://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/

As climate change progresses, be prepared to see more and more reefs around the world fall ill due to mass bleaching events

1.) Lundblad, Emily R., Dawn J. Wright, Joyce Miller, Emily M. Larkin, Ronald Rinehart, David F. Naar, Brian T. Donahue, S. Miles Anderson, and Tim Battista. “A Benthic Terrain Classification Scheme for American Samoa.” Marine Geodesy 29.2 (2006): 89-111. Web.

2.) Wilkinson, Clive R. Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2008. Townsville, Australia: Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, Reef and Rainforest Research Centre, 2008.

3.) Global Coral Bleaching. Underwater Earth, 2015. Web. <http://www.globalcoralbleaching.org/>.

4.) Global Coral Bleaching. Underwater Earth, 2015. Web. <http://www.globalcoralbleaching.org/>.

5.) Aeby, Greta, Thierry Work, and Eva Didonato. Coral and Crustose Coralline Algae Disease on the Reefs of American Samoa (2005): 1-25. Web.

6.) “NOAA Coral Reef Watch Homepage.” NOAA Coral Reef Watch Homepage. US Department of Commerce, n.d. Web. 18 Feb. 2016.