The year 2015 was the hottest on record, according to statistics from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. The year 2015 was also the year that NOAA scientists announced that the world is experiencing its third global bleaching event, where an estimated 38% of corals worldwide could be affected, threatening the state of coral reef ecosystems and the people that rely on them.1 Coral bleaching remains visibly indicative of climate change and local stressors because corals and their symbioses with dinoflagellate algae is a fragile and complex system.

To understand what bleaching is, it is relevant to understand the symbiosis between corals and the dinoflagellate algae that live in their tissues. These algae, also called zooxenthellae, or Symbiodinium, and corals have a mutualistic relationship, whereby their living together benefits both partners. Most stony, shallow, reef-building corals of the order Scleractinia have zooxenthellae while soft corals and deep-water corals generally do not. Corals capture planktonic food and excrete nitrogenous waste that is recycled by zooxenthellae and used for coral growth. Zooxenthellae are autotrophic and provide carbon for building the corals’ skeleton and produce sugars and starches for the coral by means of photosynthesis. The coral provides shelter and a fixed habitat for the zooxenthellae.

Environmental stressors and increased anthropogenic factors can easily disturb this key relationship and result in corals releasing their zooxenthellae.2 Interestingly enough, symbiodinium live in habitats 1-2°C below temperatures that cause stress and bleaching.2 Bleached coral appears pale and there is little to no pigment left in its tissues. Coral colonies are able to recover if the influx of warm temperatures dissipates, however; prolonged periods of warm temperatures will most likely cause too much damage to corals and they will become diseased or die3.

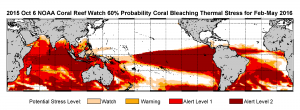

The Seychelles is an archipelago of islands off of the coast of East Africa in the Indian Ocean that is home to a diverse array of coral communities. The Seychelles faced the brunt of the widespread El Niño induced warming and subsequent global bleaching event in 1998 and experienced 90% loss of coral cover.4 An El Niño has again occurred in the past year. The large swath of hot water temperatures in the Pacific that are indicative of coral bleaching has been nicknamed, “The Blob,” and this kind of warming is predicted to occur in the Indian Ocean during the spring and summer of 2016.5 The predicted graph above is particularly worrisome because it shows a 60% probability of Alert Level 1 and Alert Level 2 warming events occurring across the Indian Ocean and these temperatures are very likely to cause another bleaching event in the Seychelles, which is still recovering from the devastating effects of the 1998 bleaching event.5 Read my next blog entry to learn more about the status of recovery in the Seychelles and how reef composition changes in response to bleaching events.- “El Niño and the 2014-2016 Global Coral Bleaching Event.” NOAA Satellite and Information Service. 2016. http://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/satellite/analyses_guidance/enso_bleaching_97-99_ag_20140507.php.

- Sheppard, Charles R.C., Simon K. Davy, and Graham M. Piling. The Biology of Coral Reefs. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Wilkinson C, O. Linden, H. Cesar, G. Hodgson, J. Rubens, and A.E. Strong, 1999. Ecological and socioeconomic impacts of 1998 coral mortality in the Indian Ocean: An ENSO impact and a warning of future change? Ambio 28, 188-196.

- Graham, N. A. J. et al. Dynamic fragility of oceanic coral reef ecosystems. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8425–8429 (2006)

- “NOAA Declares Third Ever Global Coral Bleaching Event.” NOAA. October 8, 2015. Accessed February 18, 2016. http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2015/100815-noaa-declares-third-ever-global-coral-bleaching-event.html.

- http://www.worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/africa/sc.htm 18 Feb. 2016