In my last post, we analyzed some impacts of reef fishing, such as bolstering local economies while simultaneously overexploiting specific reef fish species. In order to complete our discussion of this topic, we will be taking a deeper look into potential solutions that could account for the negative aspects of reef fishing.

In regards to a more local solution, daily catch quota systems could be implemented that would prohibit fishermen from completely overexploiting specific reef fishes.1 Using survey data on the different species that inhabit each reef, local reef conservation groups could determine exactly what the daily quota for each fisherman should be. Personally, I like this method because it would allow for all parties involved—reef organisms and fishermen—to benefit. Yes, fishermen would not be able to capture as many fish as they would like; but at least, they would still be able to make some sort of financial profit. That being said, my qualms with this specific method lies in its level of feasibility. It would not be an easy solution to enforce unless some sort of security measure was also implemented.

Recall my first blog post in which I shed light on various harmful fishing techniques, such as explosive fishing and cyanide poisoning. By restricting the employment of these fishing techniques, we would be able to limit the amount of unnecessary damage that coral reefs are being subjected to. Under no circumstance should fishing ultimately lead to complete coral death. While the aforementioned techniques make it less laborious for fishermen to do their jobs, it would be remiss to not acknowledge that such damaging techniques totally undermine all coral reef conservation efforts. As was mentioned in the previous paragraph, some type of enforcement would have to be instituted in order to make sure that fishermen actually implemented this solution.

Another solution worth highlighting would have to be restocking. While the name basically says it all, this technique involves introducing specific reef fishes to coral reef environments where they have been overfished. Recently, this has been done with groupers, snappers and rockfishes.1 While many people think this solution is a step in the right direction, I am very hesitant to get behind it. In my opinion, the only way for this solution to be impactful would be if a MASSIVE amount of fish were dumped in the reefs. Furthermore, conflicting data exists regarding how well introduced fish thrive when transplanted to reef environments. Some researchers argues that introduced fish tend to have higher mortality than their native counterparts.2 However in a study conducted by Roberts et. al., they determined that Hatchery-Reared Nassau Groupers tend to thrive when introduced to coral reef environments at large body sizes.3 Figure 1 provides us with a visual representation of the reef species at the center of the aforementioned study.

Figure 1. Image of the Nassau Grouper. It is currently being reared in hatcheries before being placed in coral reefs where its numbers are limited.©

Source: The Department of Environment and Natural Resources 4

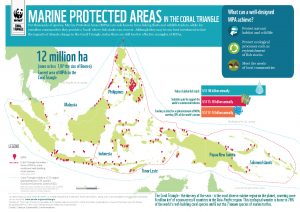

In the coral reef conservation sphere, the best known overfishing solution would have to be the implementation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which “designate areas closed for fishing.”1 This allows for specific reef areas to restore themselves in various facets, such as biomass and diversity levels. While promising, this solution is fairly challenging to implement because in order to reap the benefits of such a solution, the MPA would need to be very large. This is something that many locals would not be open to given that it would negatively affect their livelihoods to a large degree. Furthermore while proving advantageous in the long-term for sedentary species, this solution does not take into account how it will keep migratory fishes from leaving the area since they are essential to reef restoration.1 Figure 2 labels the various locations of MPAs in the coral triangle, the most diverse marine region on Earth.

Figure 2. Image of Marine Protected Areas in the Coral Triangle. Red dots denote MPA location. MPAs are the best solutions for combating overfishing, yet they remain severely underutilized.©

Source: WWF 5

Over the course of this blog series, we examined the topic of reef fishing, weighed the pros and the cons associated with it and finally concluded by putting forth some potential solutions that could be implemented in order to mitigate its negative effects. While we examined the issue in great detail, I encourage you to do your own research and come up with ways that you could help with solving this problem. I’m well-aware that this issue may seem above your heads, but coral reef conservation is a topic that should be on all of our minds. Let us make a difference while we still can. Whether big or small, change is change!

References:

1 Sheppard, C., Davy, S. K., & Pilling, G. M. (2012). The biology of coral reefs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2 Garrido, S., Santos, A., Hamadou, R., & Ferreira, S. (2015). Born small, die young: Intrinsic, size-selective mortality in marine larval fish. Scientific Reports, 5. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/srep17065.

3 Roberts, C. M., Quinn, N., Tucker, J. W., & Woodward, P. N. (1995). Introduction of Hatchery-Reared Nassau Grouper to a Coral Reef Environment. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 15(1), 159-164.

4 Lucas, R. (2012). NASSAU GROUPER (EPINEPHELUS STRIATUS) [Digital image]. Retrieved from http://environment.bm/nassau-grouper/

5 WWF. (2011). INFOGRAPHIC: Marine Protected Areas in the Coral Triangle [Digital image]. Retrieved from http://wwf.panda.org/?201819/Infographic-Marine-Protected-Areas-in-the-Coral-Triangle