Halo’s on Reefs…Could this be a sign of the angels coming to save the coral reefs in the Caribbean? Wrong.

My previous posts have focused on diseases that affect corals in the Caribbean and as you may have deduced from the similarity in the titles, this one will be no different. Today’s disease focus will be the Yellow Band (also referred to as Yellow Blotch) disease. The name is acquired from the circular band that is found on the infected corals. The disease is characterized by yellow colored blotches on the coral that continue to spread in an o-ring shape as seen in Figure 1.1 As the old infected coral is left in the middle of the halo, it begins to fill with algae and sediment.

Figure 1. Yellow Band Disease affecting a Montastraea faveolata Copyright. “Yellow Band-Disease Overview.” Common Identified Coral Diseases. NOAA, n.d. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

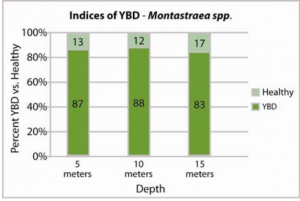

On an individual scale the tissue loss due to Yellow Band Disease (YBD) is minimal, only accounting for a couple centimeters per year. However, the issue lies in the fact that it is affecting large, century old colonies that provide the basis of some marine ecosystems in the Caribbean.1 The affected species include Montastraea annularis (Boulder star coral) and Orbicella faveolata (Mountainous Star Coral).2 A study was done in Bonaire, an island in the Caribbean to determine the amount of coral affected by YBD. In Figure 2, we see the results of the study showing that more than 80% of the Montastraea species, are affected by the disease.3 The coral in this area has been affected since 1997, and has not been able to recover since.3 This is a prime example of how this disease is affecting corals in the Caribbean.

Figure 2. Results for survey of Montastraea species in Bonaire. Across all depths it is clear the coral is greatly affected.

(Important note: “Healthy coral” is that unaffected by YBD, but it can have other diseases or deterioration) Copyright. Richards Dona, A., J.M. Cervino, V. Karachun, E.A. Lorence, E. Bartels, K. Hughen, G.W. Smith, and T.J. Goreau. “Coral Yellow Band Disease; Current Status in the Caribbean, and Links to New Indo-Pacific Outbreaks.” 11th International Coral Reef Symposium 7 (n.d.): n. pag. Reef Relief. 7 July 2008. Web.

In a study done by Cervion et al. (2004) they identified the bacteria present in healthy coral versus that affected by YBD. Their results showed that there was a prevalence of Vibrio bacteria in infected corals.4 This was reconfirmed by another experiment done in 2008.5 This provides more hope than research done on other coral diseases. Since the culprit is now identified and confirmed, scientists can now focus on ways to attack this bacteria and protect corals.

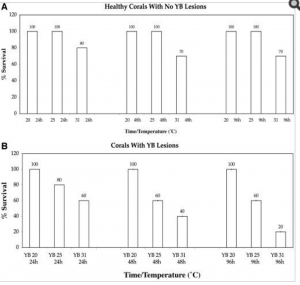

Furthermore, these studies suggest that this disease may not actually affect the coral tissue directly but rather it targets the algae (zooxanthellae) that have a mutualistic relationship; where they rely on one another to survive. The zooxanthellae releases chemicals that affect the bacteria and mucus composition that lies on top of the coral.4 In the experiments, it was proven that the lack of color was due to the loss of the zooxanthellae. The affected coral tissue could survive if it was removed from stressful environmental conditions. However, when exposed to high water temperatures and infected with YBD, the tissue would also begin to die off and the coral skeleton would be visible.4 These findings lead to the conclusion that a rise in sea surface temperature (SST), causes the disease and deterioration of the coral to spread more rapidly.

Yellow band disease signs can sneakily camouflage amongst bleached corals. Coral bleaching occurs when corals are put under stressful environmental conditions (ie. Warm waters). In response they excrete the zooxanthellae that lives within them.5 This causes the coral to lose its color and be more vulnerable and susceptible to disease. So, due to the similar discoloration patterns, if a coral is affected by both the YBD and bleaching it is hard to distinguish the two. Both of these attacks on corals are affected by higher SST and when combined the survival rate of the coral is much smaller, sometimes going down by 40% (see Figure 3).4/5

Figure 3. Results of relationship between high temperatures and YBD. a) Coral will expel some of their zooxanthellae and survival will decrease b) When affected with bacterial infections, the survival rate is much lower due to higher zooxanthellae degradation. Copyright. Cervino, James M. et al. “Relationship of Vibrio Species Infection and Elevated Temperatures to Yellow Blotch/Band Disease in Caribbean Corals.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70.11 (2004): 6855–6864. PMC. Web. 23 Apr. 2017.

The rise in SST is due to the global climate change and ever increasing temperature of the Earth. This is due to the depletion of the ozone (protective) layer of the Earth’s atmosphere. This is exacerbated by human actions. A recurring theme in my posts is that humans even if indirectly play a role in the depletion of coral reefs. However, we can also play a role in the conservation and protection. For one last time, I urge you to take action and be a proactive citizen. You do not have to be a marine biologist or participating in extensive scientific research to make a difference. Reduce. Reuse. Recycle. Learn more about coral reefs and other in danger ecosystems. Reduce energy and water waste. Avoid using plastic. Please, please just stay informed and lead a more eco-friendly lifestyle.

References

1. “Yellow-blotch/Yellow-band Disease.” Reefball. N.p., 2016. Web. 19 Apr. 2017. <http://www.reefball.org/coraldiseaseoffline/YELLOW.HTM>.

2. “Yellow Band-Disease Overview.” Common Identified Coral Diseases. NOAA, n.d. Web. 19 Apr. 2017.

3. Richards Dona, A., J.M. Cervino, V. Karachun, E.A. Lorence, E. Bartels, K. Hughen, G.W. Smith, and T.J. Goreau. “Coral Yellow Band Disease; Current Status in the Caribbean, and Links to New Indo-Pacific Outbreaks.” 11th International Coral Reef Symposium 7 (n.d.): n. pag. Reef Relief. 7 July 2008. Web.

4. Cervino, James M. et al. “Relationship of Vibrio Species Infection and Elevated Temperatures to Yellow Blotch/Band Disease in Caribbean Corals.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70.11 (2004): 6855–6864. PMC. Web. 23 Apr. 2017.

5. Cervino, J.M., Thompson, F.L., Gomez-Gil, B., Lorence, E.A., Goreau, T.J., Hayes, R.L., Winiarski-Cervino, K.B., Smith, G.W., Hughen, K. and Bartels, E. (2008), The Vibrio core group induces yellow band disease in Caribbean and Indo-Pacific reef-building corals. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 105: 1658–1671. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03871.x