Richard Branson, controversial British business magnate and founder of the Virgin Group, is already known for his massive, unorthodox, and multi-million dollar projects. The billionaire has attempted to commercialize civilian space travel, broken records for hot-air ballooning, and he has just completed his latest project: creating an artificial reef using a historic ship complete with an 80-ft kraken sculpture. The project, which was sunk on April 10th in the British Virgin Islands, is supposed to support swimming education in the BVI, increase awareness for marine conservation, provide scientists with a new study site, and generate revenue for repairs through tourism to the dive site.1

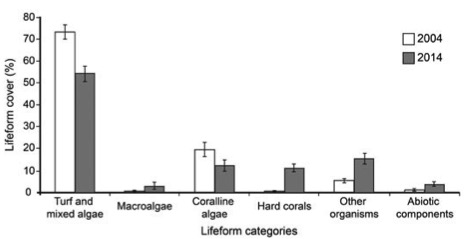

An artificial reef is, “a manmade structure that may mimic some of the characteristics of a natural reef” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,2 and they are often used for fisheries, commercial dive sites, or marine ecosystem conservation. Artificial reefs have been around for hundreds of years, but it wasn’t until the 1960’s that the United States government began researching artificial reefs in earnest.3 Today, artificial reefs are made up of specially made concrete or fiberglass structures, sunken ships, sculptures and artwork, subway cars, and more. But are these having any effect on coral recruitment and growth, or is this just another way for humans to dispose of their junk? A 2016 study analyzed artificial reefs off of the coast of Singapore after a ten-year gap in monitoring. The scientists found that these reefs had successfully recruited stony corals, and they pointed out that these corals had reached sexual maturity and could participate in mass spawning events, which is crucial for reef growth and conservation. The figure below shows the changes in species composition before and after the ten-year gap, with a promising increase in hard coral cover.4

Figure 1. The percentage cover on exterior walls of artificial reefs in Singapore in 2004 and 2014, by lifeform category. This figure shows changes in species distribution over time, with a slight decline in some algae and a notable increase in hard corals. Source: Ng et al in Aquatic Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst

Another paper showed that large artificial reefs can support diverse and abundant coral and fish communities at higher percentage coral cover than nearby natural coral reefs in Dubai. However, artificial reefs had lower coral diversity, which highlights the need to conserve natural coral reefs instead of replacing them entirely with artificial reefs.5 The high coral cover does provide an opportunity, however, to grow coral for transplantation later, or as hubs of reproduction.

There is a lot to consider when attempting to sink giant terrestrial objects as artificial reefs. Contamination of ocean waters and stability on the ocean floor are both huge risks, as these reefs can actually do more harm than good if not properly prepared. Ships have to be cleaned out to remove any substances that can contaminate waters, and certain materials, like rubber tires, can leak chemicals into the water and cause physical harm to existing reefs.6 Now, the United States has a National Artificial Reef Plan, which strictly limits what is thrown to the bottom of our oceans, and how. There is additional concern among the scientific community that artificial reefs will distract efforts away from conserving natural reefs, and warn that they can help in recovery of degraded or destroyed reefs but are second-best when it comes to conserving reefs.7 Additionally, artificial reefs can concentrate sought-after fish away from natural reefs, which makes them targets for fishing boats.6

Artificial reefs are undoubtedly only local solutions with low efficacy on a global scale, but they provide one positive solution when done correctly. Artificial reefs will never be able to fully replace coral reefs, as such a project would be far too expensive, disruptive, and the species diversity may never reach natural levels. However, they provide hope as they can be used as places for fish species to take refuge as corals continue to die off, and once coral species on these artificial reefs reach sexual maturity, they can contribute to the growth of natural reefs as well.

Lastly, I want to provide tips on how to contribute to coral reef conservation as an individual. If you want to get involved in reef conservation, look for local groups promoting beach cleanups or educational events near you, stay informed on upcoming legislation and what your candidates for local government stand for. Keep an eye out for algae and beach cleanups in your area, and try to eat sustainably sourced fish. And of course, reducing your CO2 consumption and overall living an environmentally friendly life will benefit the ocean as well as various other ecosystems. 8 We can’t all spend millions of dollars to sink giant ships or designate large swaths of ocean as Marine Protected Areas, but we can still try to make a positive human impact on our oceans.

Works Cited

- Ekstein, Nikki. “Richard Branson’s Latest Travel Project Is Underwater.” Bloomberg, April 7, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-07/richard-branson-opens-b-v-i-art-reef-scuba-dive-site.

- National Ocean Service. “What Is an Artificial Reef?” Ocean Facts, January 23, 2014.

- “A Brief History of Marine Artificial Reef Development in U.S. Waters.” Powerpoint presented at the NOAA/ASMFC Artificial Reef Workshop, Alexandria, VA, June 9, 2016.

- Ng, Chin Soon Lionel, Tai Chong Toh, and Loke Ming Chou. “Artificial Reefs as a Reef Restoration Strategy in Sediment-Affected Environments: Insights from Long-Term Monitoring.” Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, January 1, 2017, n/a-n/a. doi:10.1002/aqc.2755.

- Burt, J., A. Bartholomew, P. Usseglio, A. Bauman, and P. F. Sale. “Are Artificial Reefs Surrogates of Natural Habitats for Corals and Fish in Dubai, United Arab Emirates?” Coral Reefs 28, no. 3 (2009): 663–75. doi:10.1007/s00338-009-0500-1.

- Harrigan, Stephen. “Relics to Reefs: Why Fish Can’t Resist Sunken Ships, Tanks, and Subway Cars.” National Geographic, February 2011. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/02/artificial-reefs/harrigan-text.

- Sheppard, Charles R. C., Davey, and Graham M. Pilling. “Restoration of Reefs.” In The Biology of Coral Reefs, 297–99. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Correa, Adrienne S. “Reef Solutions” Coral Reef Ecosystems, 13 April 2017, Rice University, Houston TX. Class Lecture.