You may be used to hearing about damsels in distress but, as you’ll see, damselfish do not necessarily fit this cliché. To give a little background, damselfish are herbivorous fish that have actually been known to be a key beneficial component of their native reef ecosystem. Damselfish, shown in Figure 1, originate from the Indo-Pacific region and have recently been introduced into the Gulf of Mexico possibly through aquarium releases and ballast water.1 Now, this can be troublesome because damselfish are not native to the Gulf of Mexico region. The damselfish could potentially be a cause distress. But how do we know if the damselfish is likely to become a dangerous invasive species? Well, let’s take a look.

Figure 1. Image of young yellowtail damselfish. Flickr2

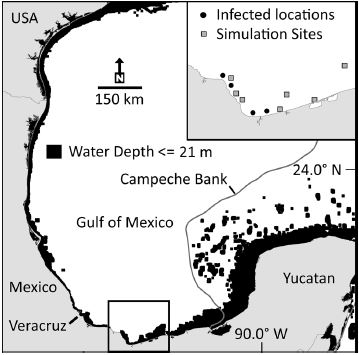

The damselfish seems to have limited dispersal in the Gulf of Mexico area, which may be a good sign. According to a study conducted by Robertson et al., the damselfish have, so far, only spread to the southwest Gulf of Mexico and do not seem to be present in the northwest Gulf of Mexico or Southeast Florida.1 Although the damselfish may have only spread to the southwest Gulf of Mexico, they have established a self-sustaining population on reefs near Veracruz, and it is not the presence that is most concerning, but the fact that the population is self-sustaining that is of highest concern (Figure 2).3 This means that the population is successful at reproducing and has managed to thrive in conditions it is not native to, without the aid of any other species; it has acclimated to this new environment pretty well.

Figure 2. Map of the Gulf of Mexico region. The boxed off section near Veracruz is then blown up on a larger scale in the box located on the upper right corner. The box in the upper right corner shows locations infected with established damselfish populations, represented by black dots. It also shows simulation sites from Johnston and Akins’ simulation experiment, represented by grey squares. Marine Biology3

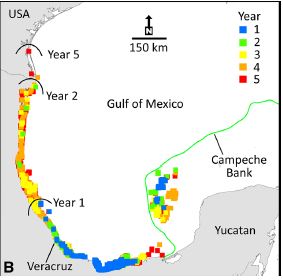

What does this mean for the coral reefs of the Veracruz region and how will the native fish be affected? Well, although the lionfish and damselfish share similar native habitats, they do not necessarily have the same effect on the habitats they have invaded. As I mentioned in my earlier post, lionfish played a large role in causing the decline in the native fish biomass of the US Atlantic coast by predating on the native fish. The damselfish do not have such a dramatic impact on the regions they have successfully populated. But, with the introduction of a new species, the reef make-up is bound to change in some sort of way. While the damselfish may not be predators like the lionfish, they are competing with native fish for habitat.3 Potential expansion of the damselfish population in the Gulf of Mexico could therefore be harmful to the native reefs. A simulation conducted by Johnston and Akins shows that in 5 years, the Veracruz reefs will face increased invasion pressure from damselfish, and this can be seen in Figure 3.3 The likelihood of the expansion of the non-native damselfish is high enough for us to be concerned.

Figure 3. Map of Gulf of Mexico, showing simulated settling locations of larvae over a period of 5 years. Year 1 represented by blue, year 2 represented by green, year 3 represented by yellow, year 4 represented by orange, and year 5 represented by red. Marine Biology3

Further research on the damselfish population in the Gulf of Mexico could help us gain a better understanding of the impacts of the non-native damselfish on the Atlantic reefs. Assessing the mode of introduction, population monitoring, and observing ecological interactions with native fish could be points of focus for further studies on the non-native damselfish in the Gulf of Mexico.1 It may be easy to overlook the risk involved with established non-native fish populations, especially when we are viewing these populations in their early stages of expansion – a mistake we made with the invasive lionfish.3 For this reason, it is imperative to pay close attention to non-native fish populations and anticipate the potential damage they can do to native habitats.3 Management strategies should be implemented earlier rather than later, in order to prevent extreme damage. We should be keeping an eye on this damsel, who knows if we have an invader on our hands? An invasive species does not have to be an “apex predator” to have a negative impact on a reef, even a fish as small as the damselfish can disrupt the balance of the reef ecosystem by taking on the role of a new competitor.4 Even though the damselfish may not be considered invasive yet, since its population numbers are not large enough, it does have the potential of becoming an invasive species in the Gulf of Mexico.

According to Johnston, the damselfish is “just one of at least 40 marine aquarium fish that have been documented in the tropical Atlantic”.4 We, as humans, have had a large impact on the introduction of these 40 different new species. Introduction of invasive species through aquarium trade is only one example. With this last blogpost, I want to remind you to pay attention to things that are going on around you. Acknowledging the influence humans have on the habitats surrounding us, especially marine habitats that we do not get to see on a daily basis, is one step towards preserving our beautiful oceans and reefs. Take action and stay involved, whether that be through directly getting involved in conservation or just by reading a few blogposts about invasive species. Ignorance is not bliss, and now is the time to take action and rectify the damage that has been done to reef ecosystems worldwide.

Resources:

1Robertson, D. Ross, et al. “An Indo-Pacific damselfish well established in the southern Gulf of Mexico: prospects for a wider, adverse invasion.” Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation 19 (2016): 1-17.

2DoctorJB. “Juvenile Yellowtail Damselfish.” Flickr. Yahoo!, 05 Feb. 2008. Web. 19 Apr. 2017. <https://www.flickr.com/photos/doctorjb/2243490200/in/photolist-4qfttw-8uBcAk-4bn3R7-stuW8c-6o6dtj-cVriHG-dT2zd8-kBmTVK-qwYf1J-k7JoaJ-8wvXHT-4WGdJq-6pEqVL-3Qb2Ep-jhseKD-f3en2U-5SGUny-77iiYM-6QaNtP-77nf4S-aJNyjB-2pGtGv-c81gGo-dLjSyo-9G9cRp-dTMe15-9Gc7WN-ehgGMi-7wbv4S-56GDJE-75hpjq-5TjbnW-7oPjpd-p7UxQs-9BzveJ-aFbM43-83UuXF-bfYPzZ-drjz7d-JYEm2-bCDBnz-6yjkeh-7VRzPh-n3GkAZ-fnXAy7-nUh2ef-5T3DPQ-fn4nQc-bnyAxH-SXrK4b/>.

3Johnston, Matthew W., and John L. Akins. “The non-native royal damsel (Neopomacentrus cyanomos) in the southern Gulf of Mexico: An invasion risk?.” Marine biology 163.1 (2016): 12.

4Nova Southeastern University. “Potential invasive species identified in S. Gulf of Mexico: Research shows non-native damselfish in part of Gulf.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 19 January 2016. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/160119141800.htm>.