Now that I’ve introduced the Flower Garden Banks in a broad sense, I can get into the specifics of the conservation status of this National Marine Sanctuary. It’s pretty much common knowledge at this point that globally, coral reefs are not doing very well. A variety of factors, many of which can be traced back to human influence, are altering the very fragile balance of abiotic and biotic conditions that coral reefs depend on for survival and growth. Last week, I established that the Flower Garden banks were special in that they remained pristine compared to other reefs around the world: seemingly unaffected by the bleaching events that plague many of these other reefs. In this post, I will discuss a recent and bizarre turn of events which contradicts the claim I made in my first post. The East Flower Garden Banks, which together with the West and Stetson Banks comprise this National Marine Sanctuary, has been undergoing a bleaching event since last summer which has caused considerable damage to the reef.

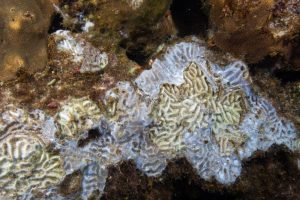

Recreational divers first noticed something was wrong in July 2016, when they discovered uncharacteristically murky, greenish waters surrounding the East Banks.1 The divers also noted large white patches splayed out on the large reef-building coral heads, and dead animals lying on the seafloor. Scientists were immediately informed about the coral die-offs, and they sent boats to extensively sample both affected and unaffected corals, along with the water in the area, and anything else that might turn up clues about the cause of the coral deaths. The extent of the damage was also surveyed, and fortunately the event did not extend to either of the other two Banks in the reef system. While only about 6% of corals at the site were affected by this event, mortality rates upwards of 70% were observed in these discrete areas.1 This doesn’t seem very high, but since this reef has historically been one of the healthiest in the region, the die-offs are quite worrisome. Many of the afflicted corals followed the same pattern of death in which the bottom section of the coral started dying and then spread up towards the top, as seen below. The same disease signs found at the East Flower Garden Banks affected some sponges on a nearby oil platform, which raised concerns that the event may have been more widespread than researchers had initially believed.1

These images, courtesy of FGBNMS/G.P.Schmahl, depict the different patterns of coral death that afflicted the East Banks last summer. Note the bottom-up pattern of death which could shed light on the nature of the die-offs.

Despite extensive sampling and effort, no definitive answer could be given for the cause of the die-offs. Temperature conditions had not been out of the ordinary. The same can be said of salinity and nutrient upwelling events.1 Shipping activity records were reviewed and ruled out the possibility that a ship could have somehow polluted the water in the area. While direct causes of bleaching events can usually be traced by looking for changes that abiotic conditions such as temperature, salinity, nutrients, and light out of tolerable ranges, no such changes were present at the East Flower Garden Banks.

Instead of these traditional causes, it could be worthwhile to examine other aspects of the reef that could have been thrown off balance. The two main coral species that form this reef are Orbicella franksi and Pseudodiploria strigosa2. We know that there are differences in the way that these corals fertilize and release their larvae into the water column: Orbicella franksi fertilizes slowly and disperses larvae across vast expanses of sea, while Pseudodiploria is more effective at settling into local areas.2 Together these corals are effective at proliferating themselves and building up the reefs that form the Flower Garden Banks. A disruption of these processes, perhaps of unknown origin, could be the cause of last summer’s die-offs. Increasing numbers of invasive lionfish at the East Banks have been documented in recent years.3 It’s possible that these lionfish, like the one pictured below, could be playing a role in disrupting the processes I just described, or otherwise have a hand in the bleaching event some other way, like bringing a disease from their native habitat that the corals are unequipped to deal with.

“Lionfish, Navarre Beach, Florida” by Dave C. This is only one of countless invasive lionfishes that are populating and spreading through the Gulf of Mexico, including the Flower Garden Banks. It’s possible invasive species like this one could be responsible for the coral deaths. (from Flickr Creative Commons)

By the time the damage had been noticed and extensive analysis had begun, it seemed as though the event had ended. Bleaching had already ceased to spread, and no additional organisms around the reef were dying at rates that were out of the ordinary.1 Last summer’s bleaching event destroyed coral colonies that have been growing for hundreds and thousands of years in a matter of days and weeks. Though scientists have still been unable to pinpoint how this event came to be, it is crucial that we understand as much as we can about the causes of this event so that we can appropriately act to end it, and prevent future events of the same nature both in the Flower Garden Banks and in vulnerable reefs around the world.

Sources:

- “Scientists Investigate Mysterious Coral Mortality Event at East Flower Garden Bank.” Scientists Investigate Mysterious Coral Mortality Event at East Flower Garden Bank. National Ocean Service, 9 Aug. 2016. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

- Davies, Sarah, Marie E. Strader, Johnathan T. Kool, Carly D. Kenkel, and Mikhail V. Matz. “Coral Life History Differences Determine the Refugium Potential of a Remote Caribbean Reef.” BioRxiv (2016): n. pag. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

- Johnston, Michelle, Marissa Nuttall, Ryan Eckert, John Embesi, Travis Sterne, Emma Hickerson, and George Schmahl. “Rapid Invasion of Indo-Pacific Lionfishes Pterois Volitans (Linnaeus, 1758) and P. Miles (Bennett, 1828) in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, Gulf of Mexico, Documented in Multiple Data Sets.” BioInvasions Records 5.2 (2016): 115-22. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.