This past month brought a lot of bad news with a slight silver lining to the corals in the Great Barrier Reef. Unfortunately, the bleaching we were starting to see at the time of my last entry only continued, worsened, and even lead to mortality in some cases. National Geographic reported 75% of the northern GBR reefs being affected by the current mass global bleaching event [1].

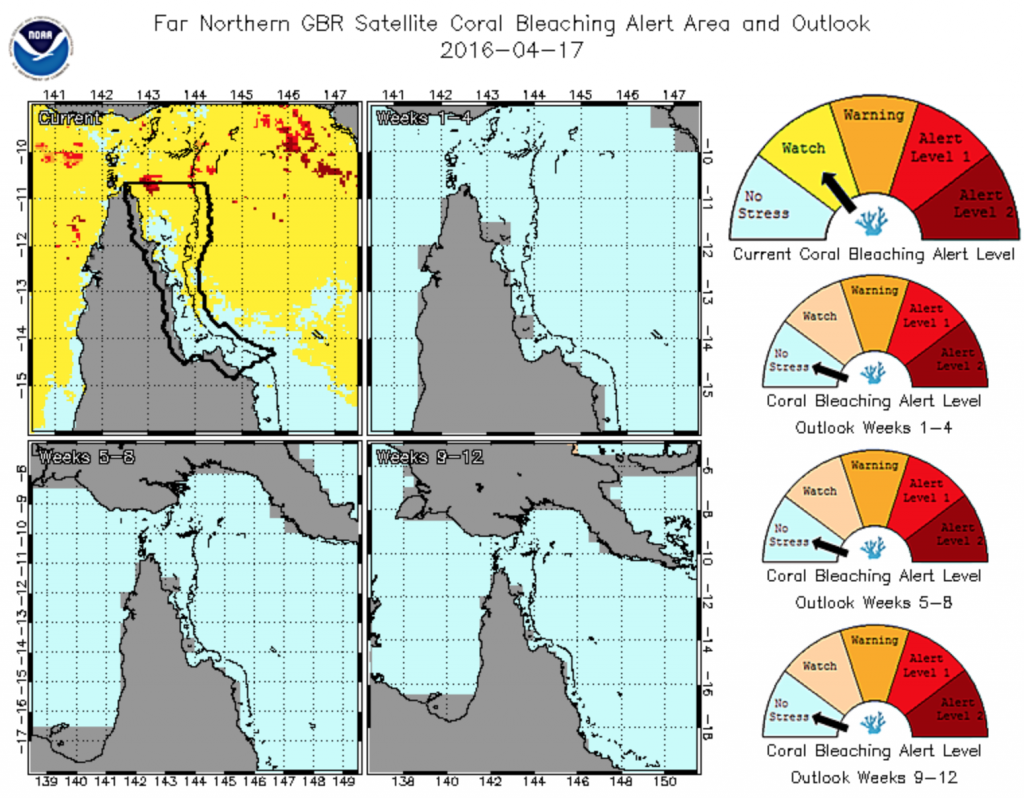

Australia’s National Coral Bleaching Taskforce reported in a survey of 520 individual reefs in the area between Cairns and Papua New Guinea that only four reefs showed no signs of bleaching [2]. Coral bleaching is not immediately a death sentence. If conditions improve (i.e. water temperatures cool down) then the symbionts that had been expelled from the coral tissue during the bleaching event can be replaced by new symbionts, and the coral can regain a healthy balance with these microorganisms and live. The truly devastating news from the bleaching in the northern GBR is that in a follow up survey to the one mentioned above, scientists reported approximately 50% of the surveyed bleached reefs exhibiting mortality [3]. While so much damage has already been done to the once pristine North GBR reefs, it looks like the bleaching event is finally over in the area. NOAA satellite predictions indicate that the area is currently at a watch level, whereas last month we saw many areas in alert level 1 and some in alert level 2. Hopefully these projections will ring true, and one week out from now the area will revert to a no stress level.

Maps depicting alert level for coral bleaching in the Northern GBR. The area remains at watch level during this week but is predicted to switch to no stress levels soon and remain there [8].

Coral cell death (bars) and Symbiodinium density (lines) at bleaching for projective, single, and repetitive bleaching [4].

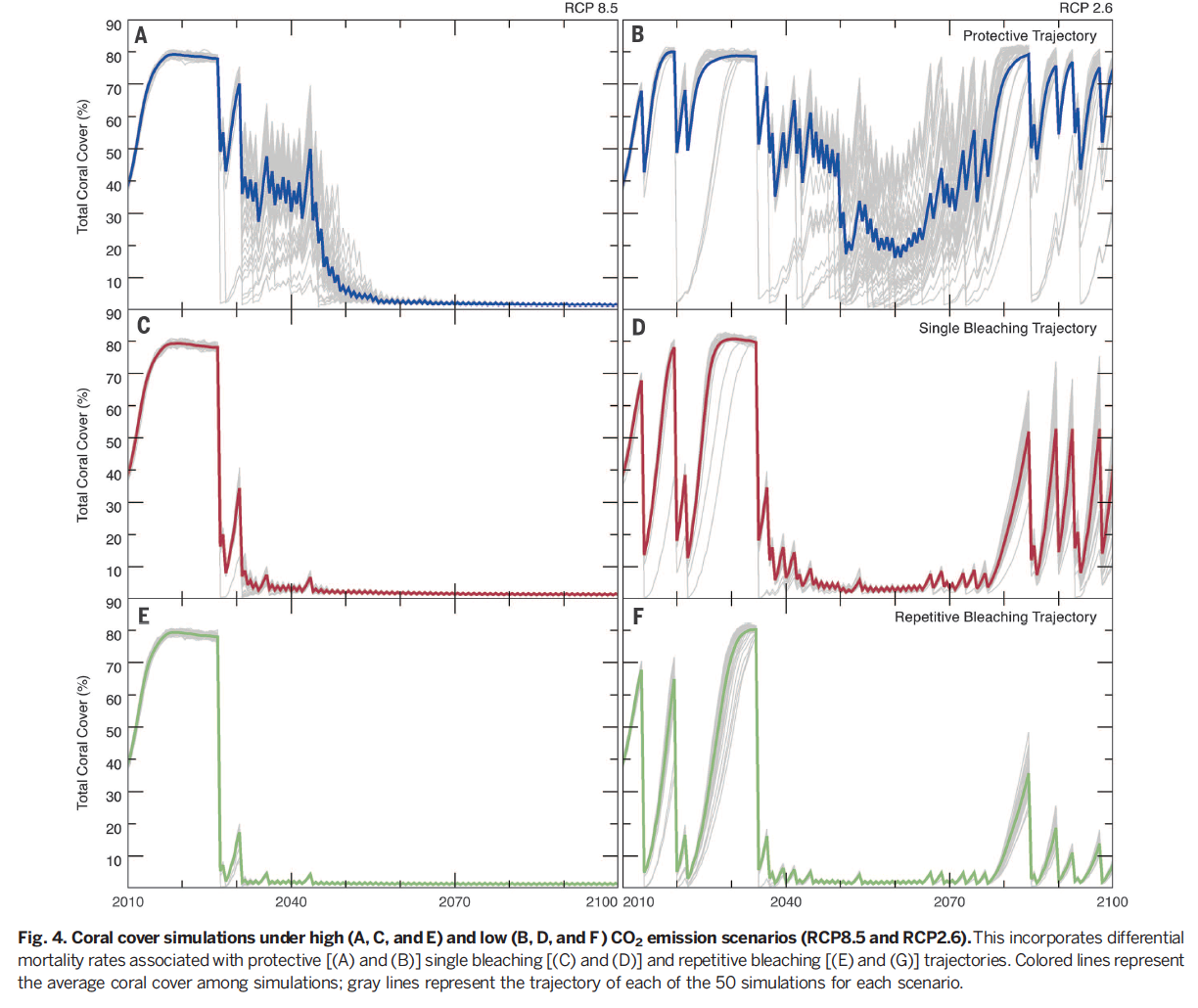

Total Coral Cover projections for the next century under protective, single, and repeated bleaching trajectories [4].

The silver lining to this situation is that at least the GBR has received notable amounts of global media coverage in the past few weeks. The New York Times ran a cover story on coral bleaching and discussed the GBR [3]. That being said, as you can see from the many other entries on this blog, this bleaching event has reached many other coral reefs all over the world that have not received the same amount of media attention. But at least the world seems to be starting to pay attention. In order to avoid the forecasts of minimal coral cover, however, more needs to be done, and quickly. This next decade will prove critical in determining the future of coral reef health. If we want to save this ecosystem, then we must act now.

Photo from aerial survey of northern GBR [7]. The GBR is the second largest coral reef area in the globe, and the northern section was the most pristine part of the reef.

References

1: Greshko, Michael. National Geographic. Web. 14 April 2016. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/04/160414-great-barrier-reef-coral-bleaching-australia-climate-change-science/

2: Arc Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. Web. 2016. http://www.coralcoe.org.au/media-releases/coral-bleaching-taskforce-documents-most-severe-bleaching-on-record

3: Innis, Michelle.”Climate-Related Death of Coral Around World Alarms Scientists.” The New York Times. 9 April 2016. Web.

4: Ainsworth, T. D. et al. “Climate change disables coral bleaching protection on the Great Barrier Reef.” Science. 15 April 2016. Web.

5: Sheppard, C. R. C. et al. “The Biology of Coral Reefs.” Oxford University Press. 2009.

6: XL Caitlin Seaview Survey. Photograph. National Geographic. 14 April 2016. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/04/160414-great-barrier-reef-coral-bleaching-australia-climate-change-science/#/01greatbarrierreefbleach.ngsversion.1460667600268.jpg

7: Terry Hughes. Photographs. ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. 2016. https://www.dropbox.com/sh/yj8tt2mj5u0inmb/AAAW6D3V0eo7YVFkqAdLzhAMa/Images?dl=0

8: Far Northern GBR Satellite Coral Bleaching Alert Area and Outlook. Image. NOAA Satellite and Information Service Coral Reef Watch. 17 April 2016. Web. http://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/vs/gauges/gbr_far_northern.php