NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) has recently declared the third ever Global Bleaching Event (1). You might have heard of Coral Bleaching, but what exactly is that? Well, first we have to understand what gives corals their colors. Stony corals, which are animals related to anemones and jellyfish, adopted a sedentary lifestyle, where they sit on a rock and grow by building their own Substrate (CaCO3), which later becomes limestone and builds the solid reef structures. But they are not alone in this process: they do it with the help of Zooxanthella, unicellular algae in the genus Symbiodinium.

The Symbiodinium cells live inside the coral colonies, in between their cells, where the algae make photosynthesis and both organisms help each other in a relation know as symbiosis (somewhat like a friendship). To make the Photosynthesis, algae carry many different photosynthetic pigments, what gives them (and the coral colonies) their multiple colors. However, when corals are under stressful conditions, such as increased temperature, their relation with the algae is disturbed, and they lose their algae friends. The result is the so called Coral Bleaching: Colonies turn white, the color of their CaCO3 skeletons, sadly now free of the algae (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Bleaching in a Colony of Siderastrea stellate, a common species in South Atlantic reefs. Picture by Beatrice P. Ferreira, available at 2.

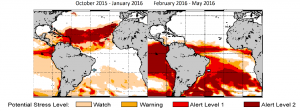

The exact reason why corals do that is unclear, but scientists know what triggers it. Most coral bleaching events are caused by changes in water temperature (3), such as those that happen during the El-Niño phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean. In fact, both previous Global Bleaching Events (1998 and 2010) happened in years with strong El-Niños, and this year, with the strongest El-Niño in decades, is not different. This phenomenon affects not only the Pacific Ocean, but also has an influence on global ocean temperatures at different intensities and times. In the Atlantic Ocean, the North portion is affected first from October to January, and South Atlantic is usually affected between February and May (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Temperature Anamalies and Bleaching Risk Map of the Atlantic Ocean. Blue arrow shows aproximate location of The Abrolhos Marine National Park. Image adapted from NOAA (1)

Reefs is South Atlantic Ocean are characterized by relatively low diversity, with only 18 coral species. However, Abrolhos Marine National Park houses all of them, being thus a very important conservation site in South Atlantic (4). Abrolhos (Figure 3) was the first Brazilian ocean National park, established in 1983. It is comprised of five islands and their respective fringing reefs (2), in addition to one isolated coastal bank reef and other smaller mushroom-shaped structures locally known as chapeirões (5). It is located 70 Km (43 miles) offshore of the Brazilian Bahia State between the latitudes 17º25’ -18º09’ South.

Abrolhos area has been affected by bleaching in the past, and those events are usually related to ocean surface temperature anomalies, like those caused in years of El-Niño (2). The first record of coral bleaching is from 1994 (6), where up to 70% of corals had some bleaching. It happened again in 1998, during the first Global Bleaching Event, and 60% of coral colonies bleached in the months of March, April and May (7), when the thermal anomalies of El-Niño affect South Atlantic. In 2003, a local ‘hot spot’ caused up to 17% of bleaching, not that bad when compared to previous ones. In 2005, again coinciding with an El-Niño, bleaching affected up to 33% of coral colonies, not surprisingly, between March and May. In 2006, a milder event occurred, with about 7% of bleaching. 2007 and 2008 where years in which some species bleached, again in the first semester of the year, with up to 90% of colonies of some species showing pigmentation alterations (3). This was the most recent bleaching event recorded in the literature for the area.

Figure 3: Abrolhos Marine National Park five islands and their fringing reefs. Picture by Marcelo Skaf, available at 8.

As a consequence of the current temperature anomalies and in the context of the current Global Coral Bleaching Event, Abrolhos Marine National Park is likely to face another Bleaching event during the following months. A study group led by Dr. Kikuchi and Dr. Leão, both professors of the Federal University of Bahia, in Brazil, is going to monitor bleaching in the Abrolhos area during the following months, and as it has been before, if it happens, they may get it on act.

——————————————–

(1)http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2015/100815-noaa-declares-third-ever-global-coral-bleaching-event.html, accessed in 14/2/2016.

(2)Ferreira, B. P., & Maida, M. (2006). Monitoramento dos recifes de coral do Brasil. MMA, Secretaria Biodiversidade e Florestas.

(3)Sassi, R., Costa Sassi, C. F., Gorlach-Lira, K., & Fitt, W. K. (2015). Pigmentation changes in Siderastrea spp. during bleaching events in the costal reefs of northeastern Brazil. Cambios En La Pigmentación de Colonias de Siderastrea Spp. Durante Los Eventos de Blanqueamiento En Arrecifes Costeros Del Noreste de Brasil., 43(1), 176–185. http://doi.org/10.3856/vol43-issue1-fulltext-15

(4)Leão, Z.M.A.N., Kikuchi,R.K. and Testa,V., (2003). Corals and coral reefs of Brazil. In Latin American Coral Reefs, J. Cortés (Ed.), pp. 9–52 (Amsterdam: Elsevier). In In Krug, L. A., Gherardi, D. F. M., Stech, J. L., de Andrade, Z. M., & de Kikuchi, R. K. P. (2012). Characterization of coral bleaching environments and their variation along the Bahia state coast, Brazil. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 33(13), 4059–4074. http://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2011.639505

(5)Rodríguez-Ramíres, A., Bastidas, C., Rodríguz, S., Leão, Z., & Kikuchi, R. (2005). The of Coral Bleaching in Southern Tropical America: Brazil , Colombia, and Venezuela. Status of Caribbean Coral Reefs after Bleaching and Hurricanes in 2005, 105–114.

(6)Castro, C. B. & Pires, D. O. (1999). A bleaching event on a Brazilian coral reef. Brazilian Journal of Oceanography, 47: 87-90.

(7)Leão, Z., Kikuchi, R., Oliveira, M., & Vasconcellos, V. (2010). Status of Eastern Brazilian coral reefs in time of climate changes. Pan-American Journal of Aquatic Sciences, 5(2), 224–235. http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044451388-5/50003-5

(8)Leão, Z. M. A. N. (1999). Abrolhos-The south Atlantic largest coral reef complex. Schobbenhaus, C; Campos, DA; Queiroz, ET; Winge, M.