Hello there. Here is my last blog post about the Galapagos coral reefs. It really has been fun following the progress of this specific reef and I hope that I’ve raised at least a tiny bit of awareness for the ever-growing threats of coral bleaching. It’s also exciting to see links to my blog posts come up in my Google searches.

Coral Reefs off the coast of Floreana Island in the Galápagos Islands photographed in 1976 (left) and 2012 (right). Photo credit: Peter Flynn and Derek Manzello

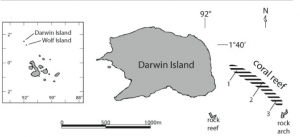

I stand by my previous post that there is hope for the Galapagos coral reefs, especially in the northern islands. The northernmost coral reef, Darwin Island, was first surveyed in 1975 and consisted primarily of frameworks of pocilloporid and poritid corals. After the 1983 El Nino caused severe coral bleaching there was near total loss of pocilloporids and extensive partial mortality of poritid corals. [1] Since the event Porites lobata, which has lower mortality rates than pocilloporid corals, has taken over as the predominant frame-building species. [1] Comparatively to pocilloporid corals, P. lobata is more thermotolerant and subsequently more successful at recruitment, making them the more resilient species. [1]

Adult lobe coral (Porites lobata) colonies can grow to be several hundred years old, providing habitat to small reef dwellers. Credit: Baums lab, Penn State University

A little bit about one of Adrienne’s favorite topics: different Symbiodinium species contribute to variations in the way corals respond to bleaching events. As a result, corals that are able to host more symbiont types are better equipped to cope with environmental perturbations. [5] In 2006, samples from the northern Galapagos Islands showed only the presence of clade C symbionts. Corals that host clade C symbionts are shade tolerant and grow faster than corals with clade D symbionts. [5] Further analysis of the distribution of Symbiodinium species in the Galapagos Islands will help us determine how the distributions influence coral persistence and coral dominance in future bleaching events. [1]

A microscopic image of Symbiodinium. Credit: Penn State University

Recent research projects have identified the Galapagos Islands as important for protecting some of the world’s most rare and vulnerable coral reefs. [2] A team of researchers took core samples from corals, examined their density bands, and produced 3-D X-ray images. [4] These images illustrated healthy annual growth rates and density patterns for corals in the northern waters. [4] New species to the Galapagos and science including zooanthid species from the genera Hydrozoanthus, Parazoanthus, Antipathozoanthus, and possibly Epizoanthus have been discovered. [2] Surveys have shown that Wolf and Darwin shelter 95% of the coral species in the Galapagos Marine Reserve, some of which are close to extinction and need special attention. [2]

The surviving reef off the coast of Darwin Island in the northern Galápagos Islands. Photo Credit: Joshua Feingold

One such project, Galapagos Coral Conservation: Impact, Mitigation, Mapping and Monitoring, aims to help the government of Ecuador protect its coral reefs around the northern Wolf and Darwin islands while minimizing its effects on the marine economy of the people of the area. [3] The project uses a variety of mapping techniques to identify areas of damaged coral. It also educates the fishing and tourism industries on ways to cause less damage to the reefs. [3]

With the help of these conservation efforts and increased awareness, coral reefs in the Galapagos have a more promising chance of recovery. I will definitely be checking up on the Galapagos reefs in the future.

Sources:

[1] Correa, Adrienne, et al. “Rapid recovery of a coral reef at Darwin Island, Galapagos Islands.” Galapagos Research 66 (2009): 6.

[2] Duff, Andrew. “Guarding the Fragile Reefs in Galapagos.” Earth and Environment. Futurity, 12 July 2010. Web. <http://www.futurity.org/guarding-the-fragile-reefs-in-galapagos/>.

[3] “International Help for the Galapagos Coral Reefs.” European Commission : CORDIS : News and Events : International Help for the Galapagos Coral Reefs. University of Southampton, 5 Aug. 2009. Web. <http://cordis.europa.eu/news/rcn/31107_en.html>.

[4] “The Galápagos Islands: A Glimpse into the Future of Our Oceans.” NOAA AOML, 2006. Web. <http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/keynotes/keynotes_0115_galapagos.html>.

[5] Simoes Correa, Adrienne. “Symbiodinium Bleaching.” Coral Reef Ecosystems. Texas, Houston. 14 Apr. 2016. Lecture.