In an earlier post, I mentioned that the Marshall Islands are currently undergoing their worst bleaching event in recorded history. Thanks to the recent observations and data of a group of scientists working in the Marshall Islands, I can now tell you about the past and current bleaching events in more detail.

This post will review the bleaching progress in the islands, other important contributing factors, and management efforts of these issues.

Bleaching Progress in the Marshall Islands

From June 2014 – January 2015, scientists observed a significant coral bleaching event [1].

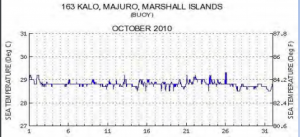

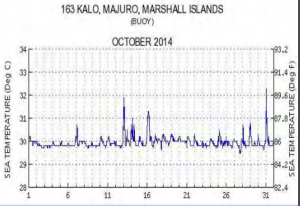

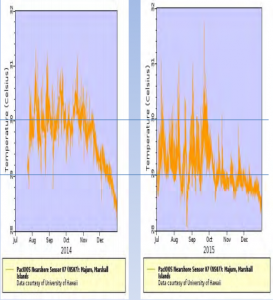

Sea temperature levels for October 2010 and 2014, showing a marked increase for 2014 sea temperature [1].

Most of the bleaching took place in late 2014, despite there being no official El Niño event. Significant bleaching was seen from August to December with little coral recovery. Below is a comparison of 2014 and 2015 sea level temperatures. They are seen to be mostly lower during the first part of the year during the 2015 moderate El Niño event. In 2015, patches of bleaching were observed through mid November [1].

Left: 2014 sea temperatures during an unofficial and weak El Niño season versus Right: 2015 sea temperatures during a confirmed El Niño event.

A rise in sea level temperature in June-October 2015 was observed due to the combination of Westerly winds and strong Easterly tradewinds [1].

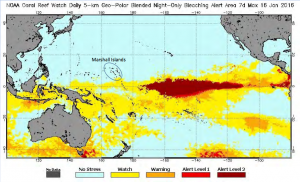

Only time and future observations will tell us how global temperature patterns will affect 2016 bleaching events. Below is a map of bleaching risk published for January 2016 with relation to the Marshall Islands.

The hard-to-read title says, “NOAA Coral Reef Watch Daily 5-km Geo-Polar Blended Night-Only Bleaching Alert Area 7d Max 16 Jan 2016”. The encircled islands in the middle of the image are the Marshall Islands.

Until further observations are made, it is important to track the progress of coral bleaching events and how the reefs have been affected so far. Following the 2014 bleaching event, it was estimated that three quarters of shallow branching corals, two thirds of table corals, and around one quarter of massive corals had been killed.

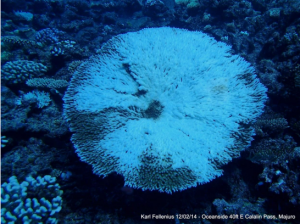

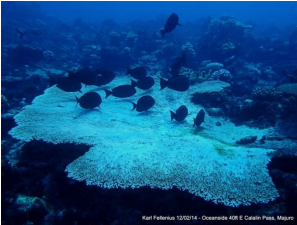

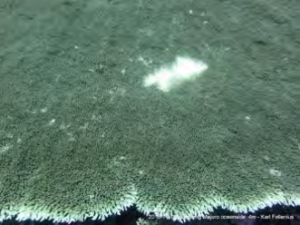

A photo of a partially bleached coral at 40 ft at southeast Catalin Pass, Majuro atoll. Half of all table corals at this location have bleached [2].

Some corals were more resistant to coral bleaching than others, however. Porites rus, a common coral around the large Majuro atoll, Porites cylindrica, and deeper growing Porites were all observed to be fairly resistant [2].

Throughout 2014 and 2015, observations of coral bleaching locations around the Marshall Islands show which corals and locations were most affected. The following pictures represent a brief timeline of the findings, focusing on the reefs surrounding two major atolls, Majuro and Arno. Both of these locations suffer from fishing pressures, however Arno is significantly more rural. Majuro in particular was chosen because it houses much of the population of the Marshall Islands, meaning the sustainability of the reef and its wildlife is essential [3]

The locations chosen for study may be referred to as “lagoon side” or “oceanside“, indicating which side of the island they are located on. Locations may also be described directionally, referring to their position relative to the entire atoll. Results were gathered using the spot check and manta tow monitoring methods as well as quadrat measuring techniques.

Two notable atolls for these studies, Majuro and Arno atolls. The observations listed below are all centered around these two atolls [1].

October 2014: reports from locals indicate coral bleaching around the Arno atoll and the Majuro atoll. Species, depth, and percentage was not recorded, however anemones were notably bleached [2].

October 2014: reports from locals indicate coral bleaching around the Arno atoll and the Majuro atoll. Species, depth, and percentage was not recorded, however anemones were notably bleached [2].

Late October 2014: Observations of the eastern end of Long Island on the South Majuro atoll reported total bleaching of all Acropora colonies. The stressed reef flat was otherwise covered in invasive Hypnea algae [2].

October-November 2014: Western end of Long Island on the South Majora atoll. Bleached corals were observed between 10-25 ft, mostly covered in green and black algae, indicating that bleaching occurred at least one month prior [2].

December 2014: Lagoon side patch reef off of north Majuro atoll, around 25% coral cover. Shallow depths had lower bleaching levels due to widespread resistant corals. Below 75 ft, three quarters of the coral cover is bleached. Pictured above at a depth of 100 ft is Acropora nasuta and an Astreopora species [2].

December 2014: East side of Calalin Pass, north Majuro atoll, 40% coral cover. The most severe bleaching occurred from 50-70 ft, where about three quarters of coral cover was bleached. Pictured above at a depth of 30 ft is a bleached Acropora species [2].

Mid-December 2014: Arno atoll is found to have cleaner water and less algal cover, but more grazers. No coral cover or bleaching data was recorded, but it is estimated that percentages would be lower than at Majuro. This suggests that reefs farther from population centers have a higher chance of recovery from coral bleaching. Pictured above is a partially bleached coral at Arno atoll.

July 2015: Oceanside Uliga East Majuro, 10% coral cover. Pocillopora species colonies display 50% bleaching on the reef flat.

August 2015: Lagoon side Airport South Majuro. Only resistant corals exist here, but bleached anemones can be seen.

August 2015: Lagoon side Landfill southeast Majuro, 15% coral cover at 9-23 ft. 30% of Pocillopora and Acropora species colonies are bleached. An example colony is pictured above.

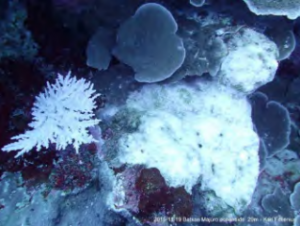

November 2015: Oceanside Batkan southeast Majuro, 10% coral cover at 16-115 ft. 30% of non-Porites colonies are bleached. Three examples are pictured above.

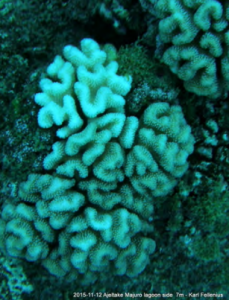

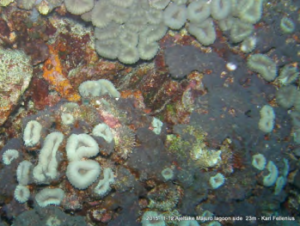

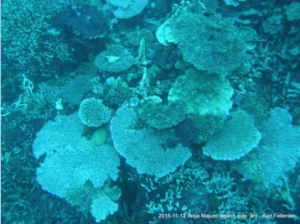

November 2015: Lagoon side Ajeltake south Majuro, 10% coral cover at 16-82 ft. 15% of non-Porites colonies are bleached. Above are two pictures of various species.

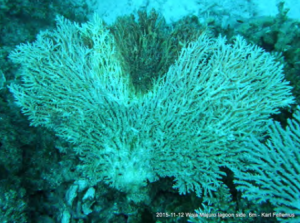

November 2015: Lagoon side Woja southwest Majuro, 15% coral cover at 20-33 ft. 10% of non-Porites colonies are bleached. Three pictures of various species are above.

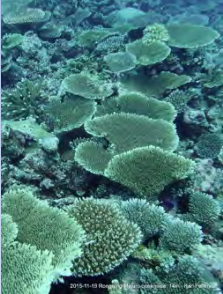

November 2015: Oceanside Rongrong northwest Majuro, 70% coral cover at 13-115 ft. This area had 5% bleaching recorded. It was also the only site not observed in previous years, but seemed to have no evidence of previous bleachings.

Contributing Factors

There are several important factors contributing to coral bleaching and the health of reefs and the surrounding island communities. These include not only coral bleaching, but also climate change, severe weather, inundation events, and over fishing.

Since the 1990s, attempts have been made to limit the rise in global surface temperature to 2°C per year. Recent studies have shown that the non-linear nature of temperature patterns will cause even a 1°C rise to be as detrimental as a 2°C rise in temperature any other year. A 2°C rise will

“far worse than double the sea level rise, coral bleaching, storms, and drought that the [Marshall Islands] experiences today” [4].

Coral reef scientists say that 1.5°C more is the upper limit for coral growth [4], and the countries that make up the Pacific Island Forum are pushing for this limit.

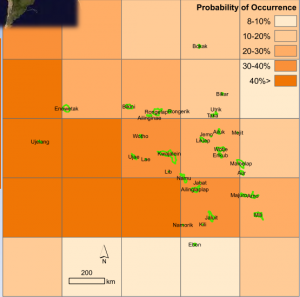

Severe weather is also an important stressor. Cyclones are common, and can cause damage to reefs through physical damage and by changing normal salinity and pH levels, but also damage island communities. Below is a map of cyclone probability in the Marshall Islands

Above: A map of the Marshall islands with underlying colors indicating the chance of cyclones. Over half the islands are at a 25% chance or above. Data from IBTrACS and Spennemann (2004).

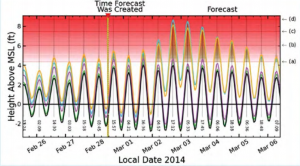

Storms and swell waves cause another phenomenon in the Marshall Islands known as inundation events. These events can range from moderate to severe flooding on the islands. Below is a 6-day inundation forecast during a period of high risk.

An inundation level forecast from Feb 26- Mar 6 of 2014. Some predictions indicate inundations of over 8 ft or as low as 2 ft [1].

Inundation events are associated with high wave energy, which can be damaging to reefs and contribute to erosion. Coral reefs are not the only ones affected by inundation events, however. As sea levels rise every year, inundation events are more and more common for the local communities living in the Marshall Islands. These floods create large amounts of property damage and decrease the amount of freshwater available on the islands.

Inundation event on March 3, 2014 on Ejit Island [1].

Inundation events are damaging to local communities as well. This image was taken following an inundation event on October 9, 2014 [1].

Over fishing is also an issue for reef life. Reef herbivores help maintain a healthy balance of algae and coral on the reefs, and efforts have been made to protect them. Organizations like the Marshall Islands Marina Resources Authority (MIMRA), the Coastal Management Advisory Council (CMAC), the Marshall Islands Mayors Association (MIMA), and local government strive to limit fishing of herbivores , especially in periods of environmental stress [5]. A 3 month closure of commercial herbivore fishing is tentative for March through May of 2016 [1].

Management Efforts

Researchers have made efforts to relocate corals away from sites where dredging is threatening coral colonies. The UH Sea Grant program relocated six large table corals and over 50 smaller colonies. The corals were moved from a site called Lojemwa on the Long Island of Majuro to a location 500 ft away that lacks coral [6]. Relocation procedure included,

“the large table corals were mostly relocated with their bases intact, and floated with locally-adapted lift bags with the assistance of a small boat. Other colonies were strategically secured on elevated reef surfaces in the new area, and smaller ones along with broken pieces inserted into wet concrete 2×2 foot forms” [6].

Above: Divers relocating pieces of Acropora digitifera. [6]

Above: A relocated table coral. This colony is an Acropora species. [6]

Above: Cement block containing relocated coral fragments. Researchers expect the cement block to be overgrown in a year, and it is currently heavy enough to withstand most swell activity [1,6].

This treatment involved the help of local divers, and in addition to saving the corals, increased local knowledge of coral life and protection.

In addition to efforts by researchers, it is important to include the efforts of others on the islands. It is difficult to quantify the importance of coral reefs to those in the Marshall Islands. Many local resources are available to both educate and assist individuals who want to protect their home, be that their physical houses on the island or the surrounding flora and fauna. Guidebooks like A Landowner’s Guide to Coastal Protection [6] prepare locals for natural hazards. Many other programs assist in conservancy on a local scale [5].

Additionally, a program called Reimaanlok has been implemented by the Coastal Management Advisory Council. Reimaanlok means “looking to the future”, and functions as a conservation framework, creating a space for conservation agencies, local organizations and government, and other interests to work together and address conservation issues [5,6].

Locals know that the reefs protect the islands. To many, protecting the coral reefs is just returning the favor.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the direction and information provided by Karl Fellenius, Dr. Peter Houk, and Dr. Matt Kendall.

Resources

[1] Hess, D., Fellenius, K. Impacts and Initiatives: Climate Change in the RMI. January 2016 Presentation to the Climate Change Working Group US Coral Reef Task Force. College of the Marshall Islands, UH Sea Grant. 2016.

[2] Fellenius, K. Republic of the Marshall Islands Coral Bleaching Report. University of Hawai’i Sea Grant, Coastal Management Extension. Dec 31, 2014.

[3] Houk, P. et al. Status of Coral Reefs across Majuro Atoll, RMI. University of Guam Marine Laboratory, Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority, College of the Marshall Islands. 2015.

[4] Fellenius, K. Threshold of 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius. University of Hawai’i Sea Grant, College of the Marshall Islands. 2015.

[5] White, R., Stege, M., Fellenius, K. Republic of the Marshall Islands Oceans and Tides Capacity Mapping Report. COSPPac. 22 pp. 2015.

[6] Fellenius, K. Coral Divers Mainstream Shoreline Protection with Dredge Site Mitigation in the Marshalls. Ka Pili Kai: Coastal Hazards, Climate Change, and Community Resilience. Vol 36, No 3. pp 14-15. 2014.